The Search For The Buddha

The men who discovered India's lost religion, Charles Allen, Carroll & Graf Publishers, New York (2002)

Prologue: The Orientalists

Section titled “Prologue: The Orientalists”- The author visits Taxila, Pakistan, reflecting on the historical destruction of Buddhist sites by Huns, Islam, and modern neglect (e.g., Bamian colossi).

- John Marshall is noted as the first modern archaeologist in Asia, excavating Taxila and the Indus Valley Civilization.

- The term “Orientalist” is discussed, particularly in light of Edward Said’s critique that it was a tool of Western imperialism.

- Allen argues that these “Orientalist sahibs” were products of the Enlightenment who initiated the recovery of South Asia’s lost past, including Buddhism.

- The book aims to tell the story of how a small group of Westerners “discovered” Gautama Buddha and his faith, restoring it to India and the world.

1 - The Botanising Surgeon

Section titled “1 - The Botanising Surgeon”- Introduces Dr. Francis Buchanan, a surgeon and botanist conducting a statistical survey of Bihar for the East India Company in 1811.

- Buchanan’s 1795 posting to the embassy in Ava (Burma) provided his first significant encounter with Buddhism.

- He obtained translations of Burmese religious texts from an Italian missionary, Padre Vincentius Sangermano.

- This led to his 1799 paper, “On the Religion and Literature of the Burmas,” the first serious English account of Buddhism.

- A subsequent mission to Nepal (1802), though restrictive, exposed him to a different form of Buddhism intermixed with Hindu deities.

- In 1811, during his comprehensive survey of Bengal, Buchanan’s journey brought him to the ruins of Bodh-Gaya in Bihar.

2 - Tales from the East

Section titled “2 - Tales from the East”- Early EICo servants’ knowledge of India came from classical sources like Megasthenes, who mentioned “Brachmanes” (Brahmins) and “Sarmanes” (Shramana, or ascetics).

- The story of the Buddha was transmitted to medieval Europe through the legend of the Christian saints Barlaam and Josaphat.

- Marco Polo provided a detailed account of “Sakyamuni Burkhan” (Buddha) and his “Great Renunciation” story, encountered in Ceylon.

- Portuguese missionaries in the 16th century encountered and tried to destroy Buddhist relics, such as the tooth relic in Ceylon, believing it idolatrous.

- Jesuit scholars like Athanasius Kircher encountered Tibetan “Lamaism” and noted its similarity to Catholic rites.

- Englishman Robert Knox, after being shipwrecked in 1659, spent decades in Ceylon and published the first detailed English account of “Buddou” worship, its monks (“Gonni-priests”), and the sacred “Bogaha” (Bodhi) tree.

3 - Oriental Jones and the Asiatic Society

Section titled “3 - Oriental Jones and the Asiatic Society”- Sir William Jones, a prodigious Welsh linguist and lawyer, arrived in Calcutta in 1783 as a Supreme Court judge.

- Jones was a prominent “Orientalist” who championed the study of Asian texts, believing them equal to classical European works.

- He found allies in Governor-General Warren Hastings and other EICo servants like Charles Wilkins, who had created the first Bengali typeface and deciphered an archaic Sanskrit inscription.

- In January 1784, Jones founded the “Asiatick Society” in Calcutta to investigate “man and nature” in Asia, serving as its first president.

- Despite early struggles, the society’s journal, Asiatick Researches, eventually became a revelation, sparking widespread interest in Indian studies.

4 - Jones and the Language of the Gods

Section titled “4 - Jones and the Language of the Gods”- Charles Wilkins’s translation of the Bhagavad Gita impressed Warren Hastings, while his 1785 translation of an inscription from “Bood-dha-gaya” first linked the site to Buddha.

- Sir William Jones learned Sanskrit and, in 1786, announced his discovery that Sanskrit, Greek, and Latin stemmed from a “common source,” founding the field of comparative philology.

- Jones and his contemporary, Francis Wilford, made significant errors by trying to fit Indian history into a Biblical timeline (e.g., Manu as Noah) or attribute Buddhist origins to Ethiopia.

- Jones’s greatest breakthrough was identifying the “Sandrokottos” of Greek texts as the Mauryan Emperor Chandragupta, and “Palimbothra” as his capital, Pataliputra (modern Patna).

- This provided the first fixed date (c. 312 BCE) for ancient Indian history and identified the Mauryan dynasty, including Chandragupta’s grandson, Ashoka.

- After Jones’s death in 1794, his work sparked an “Oriental Renaissance” in Germany but faced backlash in Britain from Evangelicals and Utilitarians like James Mill.

5 - Dr Buchanan and the Messengers from Ava

Section titled “5 - Dr Buchanan and the Messengers from Ava”- Joseph Eudelin de Joinville, surveying British-annexed Ceylon, noted the common religion of “Boudhou” in Ceylon, Burma, and Siam.

- Francis Buchanan’s 1799 paper on Burmese religion identified “Godama” (Gautama) as a historical figure, dating his death to c. 542 BCE.

- This was confirmed by papers from Ceylon (Mahony, de Joinville) detailing the life of Prince Siddhartha and the basic tenets of his faith.

- Buchanan’s 1802 mission to Nepal identified a different form of Buddhism, recognizing “Sakya Singha” as Gautama.

- During his 1811 survey of Bihar, Buchanan visited the ruins of Bodh-Gaya, which was occupied by a Hindu mahant.

- The mahant had learned from “messengers from Ava” (Burmese pilgrims) that the site was where their god Gautama had lived.

- A local convert informed Buchanan that the great Mahabodhi temple was built by King “Asoka Dharma” of Maghada.

- Buchanan also surveyed the ruins of Rajgir and Burgaon (Nalanda) but failed to realize their significance.

6 - Three Englishmen and a Hungarian

Section titled “6 - Three Englishmen and a Hungarian”- George Turnour arrived in Ceylon in 1818, learned Pali from a local monk, and began translating the island’s great chronicle, the Mahavamsa.

- Brian Houghton Hodgson, posted to Kathmandu in 1820, befriended a local pandit, Amrita Nanda Bandya, and collected hundreds of Sanskrit Buddhist texts, which he sent to Calcutta and Paris.

- Hodgson began corresponding with Alexander Csoma de Koros, a Hungarian scholar living in a Tibetan monastery in Zanskar to trace the origins of the Hungarian people.

- Csoma de Koros confirmed that the Tibetan Buddhist canon (the Kanjur) was translated from Indian Sanskrit and later moved to Calcutta to work as a librarian at the Asiatic Society.

- James Prinsep, the third figure, arrived in Calcutta in 1819 as an Assay Master at the Mint, working under Dr. H. H. Wilson, the Secretary of the Asiatic Society.

7 - Tigers, Topes and Rock-Cut Tèmples

Section titled “7 - Tigers, Topes and Rock-Cut Tèmples”- Colonel Colin Mackenzie, during his surveys, documented the great Buddhist stupa at Amaravati (1797, 1816) and, with Stamford Raffles, uncovered the Chandi Borobudur monument in Java.

- In 1820, Mackenzie found the Dauli rock inscription, noting its script was identical to the mysterious “pseudo-Greek” script on the Feroz Shah’s Lat pillar in Delhi.

- In 1818, British officers discovered the Great Tope at Sanchi (Bhilsa), describing its massive dome and intricately carved gateways.

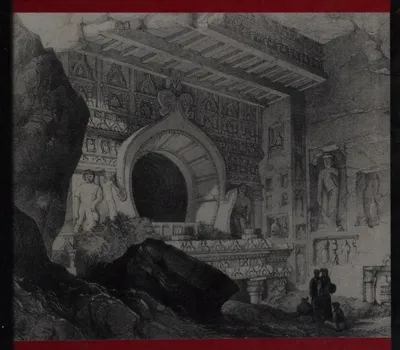

- In 1824, Lieutenant James Alexander, while tiger hunting, stumbled upon the Ajanta caves, filled with elaborate carvings and vibrant fresco paintings depicting Buddhist scenes.

- The Royal Asiatic Society (RAS) was founded in London in 1823.

- A flawed translation of the Mahavamsa, published by Edward Upham and sponsored by Sir Alexander Johnston, incorrectly identified Ceylon as the main theater of Buddha’s life, which stalled George Turnour’s work.

8 - James Prinsep the Scientific Enquirer

Section titled “8 - James Prinsep the Scientific Enquirer”- James Prinsep spent ten years (1820-1830) as Mint Master in Benares, where he undertook major scientific and civic engineering projects, including mapping the city and building a bridge.

- He returned to Calcutta in 1830 amidst a financial crash that ruined his brother’s business.

- Prinsep’s interest in Indian studies was ignited by numismatics, particularly coins recovered from the Manikyala tope by General Ventura.

- In 1833, Prinsep succeeded H. H. Wilson as Secretary of the Asiatic Society and revitalized it, launching the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal.

- His enthusiasm inspired a new network of “field archaeologists” and correspondents.

- Brian Hodgson, writing from Nepal, established for Prinsep that Buddhism originated in India as a reform of Brahmanism and identified two major, distinct traditions (later known as Mahayana and Theravada).

9 - Triumph and Disaster

Section titled “9 - Triumph and Disaster”- A Burmese inscription found at Bodh-Gaya confirmed that the temple was built by King “Athauka” (Ashoka), grandson of “Tsanda-goutta” (Chandragupta).

- George Turnour’s 1836 translation of the Ceylonese Mahavamsa confirmed Ashoka’s identity and provided a detailed, reliable chronology for Buddhism, detailing his conversion and his sending of his son Mahendra to Ceylon.

- Turnour’s work also exposed the “extraordinary delusion” of Edward Upham’s earlier, fraudulent translation.

- The “Orientalist” cause suffered a major blow from Thomas Babington Macaulay’s 1835 “Minute on Education,” which successfully argued for replacing Indian learning with English education.

- James Prinsep, Brian Hodgson, and Alexander Csoma de Koros identified the “Ye dharma…” inscription found at Sarnath and other sites as the core Buddhist “confessio fidei”.

- By 1836, the life story of Gautama Buddha—his birth at Lumbini, life at Kapilavastu, enlightenment at Bodh-Gaya, first sermon at Sarnath, and death at Kushinagar—was established, though these sites remained lost.

10 - Prinsep and the Beloved of the Gods

Section titled “10 - Prinsep and the Beloved of the Gods”- James Prinsep struggled for years to decipher the mysterious “Delhi No. 1” script found on pillars and rocks across India.

- The breakthrough came in March 1837 from short, donative inscriptions from the Sanchi tope, which allowed Prinsep to identify the word danam (“gift”) and subsequently the entire alphabet (Ashoka Brahmi).

- On June 7, 1837, Prinsep announced he could read the edicts, which began “Thus spake King Piyadasi, Beloved of the Gods”.

- George Turnour, from Ceylon, provided the final key, citing a text that stated King Ashoka was “surnamed Piyadassi.” The edicts belonged to Emperor Ashoka.

- Prinsep’s decipherment of the Girnar and Dauli edicts revealed Ashoka’s remorse over the Kalinga war and his diplomatic contact with Greek kings, fixing his reign in the 3rd century BCE.

- The intense overwork led to Prinsep’s mental breakdown; he died in 1840, aged 41.

- Prinsep’s death, along with the deaths of Turnour (1843) and Csoma de Koros (1842), and the resignation of Hodgson (1843), marked the end of the “golden age” of Orientalism in India.

- Hodgson’s manuscripts, sent to Paris, enabled Eugène Burnouf to publish the first comprehensive scholarly history of Indian Buddhism in 1844.

11 - Alexander Cunningham and the Chinese Pilgrims

Section titled “11 - Alexander Cunningham and the Chinese Pilgrims”- Alexander Cunningham, seeing himself as Prinsep’s successor, began using the translated itineraries of Chinese pilgrims to locate lost sites, identifying Samkassa in 1843 by following Fa Hian.

- After the Sikh Wars, Cunningham excavated Sanchi (1851) and discovered relic caskets inscribed with the names of Buddha’s disciples, Sariputa and Maha Mogalana, confirming the stupa’s Ashokan-era origins.

- In 1861, Lord Canning appointed Cunningham as the first Archaeological Surveyor of India.

- Cunningham used the newly translated, more detailed travels of a second pilgrim, Huan Tsang, to guide his surveys.

- In his first tours (1861-63), he definitively identified the great monastic university of Nalanda, as well as the ancient cities of Kausambi, Vaisali, and Sravasti.

- The Survey was abolished in 1865; during Cunningham’s subsequent time in England, James Fergusson re-discovered the Amaravati sculptures in London and proposed an incorrect “Tree and Serpent Worship” theory for them.

12 - Cunningham and the Archaeological Survey

Section titled “12 - Cunningham and the Archaeological Survey”- The Archaeological Survey was revived in 1870, and Cunningham returned as Director-General.

- He correctly identified the key sites at Rajgir (Pippala cave and Saptaparni Hall) described by the Chinese pilgrims.

- His assistant, Archibald Carlleyle, excavated Kasia and found the giant reclining Buddha, confirming it as Kushinagar, the site of the Buddha’s death.

- Cunningham excavated the Bharhut stupa, saving its priceless railings by sending them to the Calcutta museum for preservation.

- He oversaw the first professional restoration of the collapsing Mahabodhi temple at Bodh-Gaya in 1879.

- Cunningham retired in 1885. Later Survey work under his successor led to F.O. Oertel’s 1904 discovery at Sarnath of the magnificent Ashokan lion capital, which became modern India’s national symbol.

13 - The Welshman, the Russian Spiritualist, the American Civil War Colonel and the Editor of the Daily Telegraph

Section titled “13 - The Welshman, the Russian Spiritualist, the American Civil War Colonel and the Editor of the Daily Telegraph”- Thomas Williams Rhys Davids, a civil servant in Ceylon, was inspired by the 1873 Panadura debate to study Pali; he later founded the Pali Text Society (1881) in England.

- Sir Edwin Arnold, editor of the Daily Telegraph, wrote The Light of Asia (1879), a hugely popular epic poem based on Rhys Davids’ work, which introduced Buddhism to millions in the West.

- In 1880, Colonel Henry Olcott and Madame Blavatsky, founders of the Theosophical Society, arrived in Ceylon and publicly converted to Buddhism, galvanizing the local revival.

- Olcott organized Buddhist schools and wrote a Buddhist Catechism (1881) that promoted a rational, demystified version of the faith.

- Edwin Arnold’s 1886 visit to Bodh-Gaya horrified him, as the site was controlled by a Hindu mahant; he launched a campaign for its restoration to Buddhists.

- Olcott’s disciple, Anagarika Dharmapala, took up the cause, founding the Maha Bodhi Society (1891) to reclaim the temple, leading to a long legal and physical struggle known as the “Buddha Gaya Temple Case”.

14 - The Search for Buddha’s Birthplace

Section titled “14 - The Search for Buddha’s Birthplace”- Dr. L. Austine Waddell, studying the Chinese pilgrims’ routes, correctly identified the true location of Ashoka’s palace at Pataliputra (Patna) in 1892.

- In 1893, an Ashokan pillar was found at Nigliva in the Nepalese Terai. Waddell used its inscription (mentioning Buddha Kanakamuni) and Huan Tsang’s itinerary to predict that Buddha’s birthplace, Lumbini, and his home city, Kapilavastu, were nearby.

- Dr. Alois Führer was assigned to the official excavation. In December 1896, a second pillar was unearthed at Rumindei (Lumbini) bearing an Ashokan inscription explicitly stating, “Here was Buddha Sakyamuni born”.

- Führer falsely claimed credit for the discovery in the press and identified a site in Nepal as Kapilavastu.

- In January 1898, William Peppé excavated a stupa at Piprahwa, on the Indian side of the border, and found a relic casket inscribed by the “Sakyas” with the “relics of the Buddha,” strongly suggesting this was the true Kapilavastu.

- Vincent Smith and Peppé subsequently caught Führer planting fake inscriptions at his rival Nepalese site to support his claim; Führer was forced to resign in disgrace.

- The exact location of Kapilavastu remains disputed between the Piprahwa (India) and Tilaurakot (Nepal) sites.

Epilogue: The Sacredness of India

Section titled “Epilogue: The Sacredness of India”- Lord Curzon, as Viceroy (1899-1904), championed the preservation of India’s historical monuments, declaring that “Art and beauty… are independent of creeds”.

- He revived the Archaeological Survey of India and appointed John Marshall as Director-General in 1902.

- Marshall and his team professionally excavated and restored major sites, including Sanchi, Nalanda, and Sarnath.

- The Sarnath excavations uncovered the flawless Ashokan lion capital (now the national emblem of India) and the iconic “Preaching Buddha” statue.

- Excavations confirmed Buddhism’s decline in India was due to a resurgent Hinduism that absorbed Buddha as an avatar of Vishnu, long before the Muslim invasions.

- The 1951 Chinese invasion of Tibet led to a Tibetan diaspora, which spread Tibetan Buddhism (Vajrayana) to the West.

- Buddhism revived in India through the mass conversions of “untouchables” led by Dr. B. R. Ambedkar in 1956.

- The Bodh-Gaya Temple Act of 1949 finally placed the Mahabodhi temple under a joint Buddhist-Hindu management committee, ending the long dispute.